In my new job, I am asked to have taste.

This is unusual for me. As a history grad student, I was asked to use critical thinking. And skepticism. And cleverness. There was a certain aesthetic sense of absence when a story was half told or evidence was missing or an argument didn’t hold up. There is a texture to good history; Dan Smail (my former advisor) has it, Peter Brown has it, Lester Little has it, Caroline Walker Bynum has it in spades. A cadence, a rhythm, a satisfying gotcha or a piquant description of something one usually passes over. Good history is pleasing to read and useful to think with. How can one not develop a sense of taste for good history, after reading (well, skimming) hundreds of books and articles to pass generals? (To me, it felt like chugging fondue.) I suspect that my colleagues who are around the world working in archives are building that intuitive, aesthetic sense for good primary sources, too. Something rich, something beautifully formed that “fits” into a story just so. Some ideas are just more useful than others. Some prose is just more beautiful than others. Some ways of thinking, some expressions are stickier. [Of course the reception depends on the reader’s life story, the time of day, what one ate for lunch…(oy, I can’t help defending myself against some metaphysical such and such argument…actually, I just heard Howard Gardner speak about Beauty – capital B – the other day…another post…)].

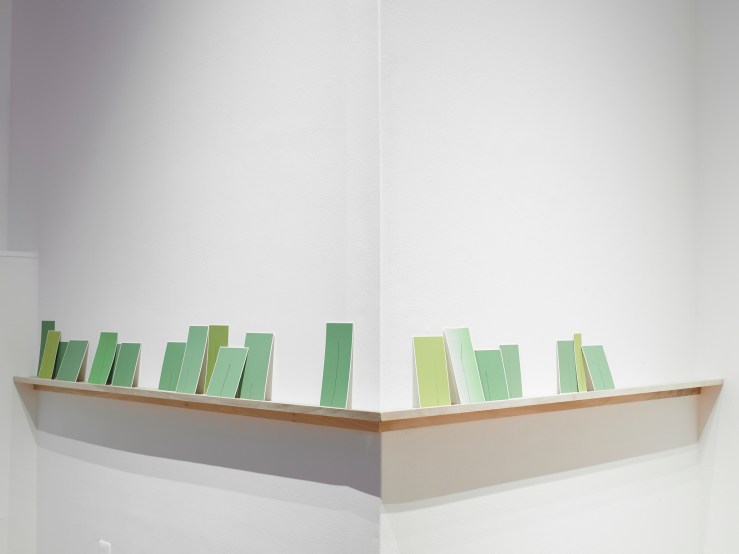

Anyway, I now find myself in a position where i have to use honest to God taste in my job. An actual sense of visual aesthetics. Like, which green panel should go where? Is that canvas warmer or cooler than that one, and should it go between these two or those two? Not only do I have to identify visual differences (which is harder for me than for an artist or art history student, someone used to looking), but I also have to use distinction and discrimination when arranging those visual objects. I arrange and swap and mould (piles of salt and pigment) and rearrange until things look good.

I do not trust my eye (yet). I have severe Imposter Syndrome. For the first time, however, this is not crippling for me. (I used to freeze up and then melt down when waves of doubt hit.) This is actually pretty stimulating. I have built a (so far short) museum career on telling other people that they can look at art, that they do have something interesting to say, that their personal responses matter. In some ways, this job is putting my most basic values about art under the microscope. Here is what I have been thinking to myself while “curatorial assisting” during this exhibition’s installation:

My response to this piece matters! But not really, because there is an art historical, canonical interpretation of what this should look like and what it should mean, and if you do not know the context of this work’s production or the reference it is making, you are dumb and uncultured. Well, no, because there is not a lot of research about this yet. It is a contemporary piece. Look, the artist is over there! Yea, but anyone who is anyone with taste will know that that should not look like that. But I like it! Why? Because it makes me feel all the things this way, and it does not the other way. But still. Do your research. You have a lot to catch up on.

My inner critic is right – I do need to do the research. I do need to develop my eye. I do need to build up a foundation, an arsenal in order to be a better, more sophisticated looker.

In Move Closer, John Armstrong recounts some stories from John Ruskin’s autobiography, when the artist would spend hours in his own London neighborhood delighting in the ordinary. Ruskin also wrote of his favorite painter Turner noticing dusty sunbeams and cabbage leaves and oranges in wheelbarrows in a dark alley-way off of Covent Garden. Writes Armstrong:

Experience of special, privileged objects is not, then, the needful thing; what counts is that the experiences are delighted in, dwelt upon, mobilized and made use of. What we need is ‘to take an interest in the world of Covent Garden’ – or whatever bit of the world it is we encounter – ‘and put to use such spectacles of life as it affords.’ It is from such experiences that deep engagement with works of art emerges. (page 37)

I sometimes wish that I had more visual acuity as a child – fewer books, more looking around. Or, that I had taken a greater interest in art-making after my short (yet triumphant!) turn as an AP Studio Art student. Or, that I had taken intro to art history in college after all. Or, or, or…

I guess I now have to be the child I wish I had been. I just have to go out there and do it. Notice the cabbages and all that.

NB: I am familiar with, but not fluent in, Bourdieu. So…I dunno. If the above sounds naive, it is. It is full of class things and gender things, too, I suppose. Maybe we’ll dig into those some day.