I used to blog about museum work on my academic website. Since that page has gone away, I am using this space to repost some of my favorite bits. These posts were written in 2012-13.

What is the role of “the expert” in inquiry-based, constructivist learning? | Originally posted February, 2013

I took a course with Shari Tishman at the Harvard Graduate School of Education about “Active Learning in the Museum.” In our readings and discussion, structure emerged as the key to successful learning experiences, both constructivist and inquiry-based. In his chapter on educational theory, George Hein makes this provocative statement:

“I believe that constructivism places more, not less, demands on the teacher to provide rich and rewarding environments in which learning can take place.” (page 39)

Nina Simon’s TedX talk deeply engages this question of structure; as Simon demonstrates, designed opportunities and special tools invite the audience to produce something meaningful. Ron Ritchhart’s “Cultivating a Culture of Thinking in Museums” fleshes out the forces shaping group culture, and many of these fall under the domain of the discussion facilitator (communicating expectations, allocating time, routines and structures).

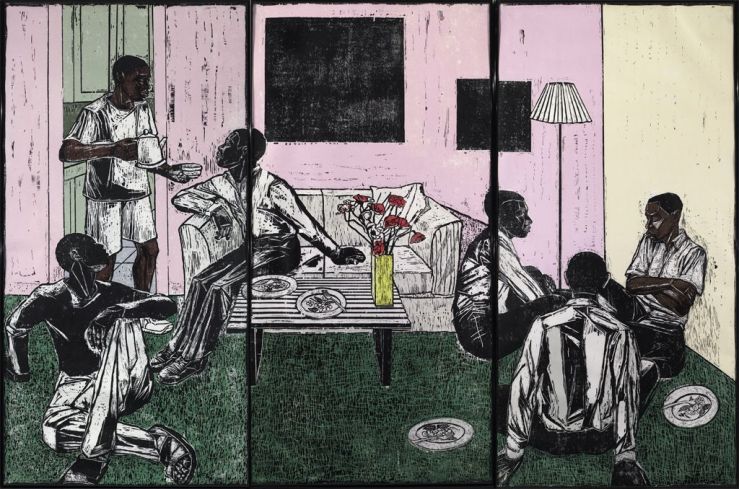

The Harvard Art Museum Task Force recently took a fieldtrip to the Gardner Museum, and we asked the education staff where rigor comes from in the VTS (Visual Thinking Strategies) curriculum. Many of the strategies are echoed in Ritchhart’s article: paraphrasing, use of appropriate vocabulary, choice of object, time and repetition. So, clearly, inquiry-based learning depends on the finesse of an experienced and committed educator. What is the role of the disciplinary expert, then? On the one hand, the role of information in inquiry is critical here. My disciplinary expertise allowed me to answer a question spontaneously asked aloud by a visitor at the Getty — I provided information, and she was intellectually satisfied. I think we agree that information can be leveraged to extend inquiry; facts are not evil in themselves. On the other hand, I am interested in habits of mind and their relationship to disciplinary expertise. In many ways, the first few years of graduate school in history is a process of enculturation: we were taught, formally and informally, to think like historians. We think about authorship and reception. We are critical of claims about universality. As a premodernist, I am especially skeptical when people throw around words like “reason” and “science” and “modernity.” This is different from the content of my expertise: it’s not fact-oriented, but rather thinking-skills-oriented. Is it possible to teach disciplinary thinking dispositions in way that is consistent with inquiry-based learning? I suspect so.

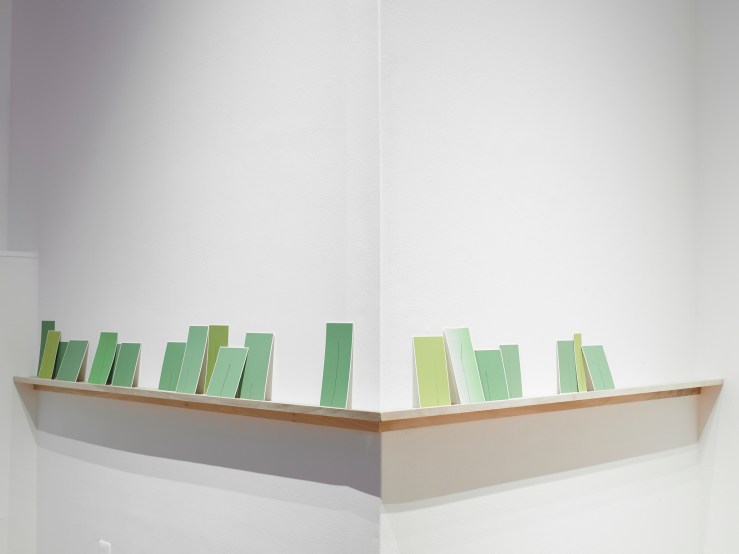

On a related note, I am getting interested in museums as sites of knowledge and sites of knowledge-production. There is a strong Foucauldian critique lurking behind this topic, of course. How do museums structure objects, space, text, and movement to create knowledge? And how self-aware are they? I suspect that exhibitions are more explicit about this than permanent installations. I would like to design a learning experience for my final project that tackles this issue, but I may be the only one in the class who is interested in this stuff. I sort of wish I were at Berkeley in the 1980s, sometimes.